A Solo UX Designer’s Guide to Survival & Impact

Advice from my years in the trenches alone.

Imagine you’re in a conference room — or, more likely, these days, a Zoom call. The eyes of several developers and a product manager fall on you. They’re waiting for your input on a complex user flow they’ve already coded. You’ve spotted several UX issues, but you’ve only been with the company for less than a month. Welcome to the life of a solo UX designer.

In recent years, there’s been a growing realization of the importance of user experience. As companies became more aware of UX’s impact, many took their first step by hiring “generalist UX designers.” They expect these designers to wear multiple hats — researcher, interaction designer, visual designer, and sometimes developer. While larger tech companies have specialized UX teams with dedicated roles, most organizations reasonably start with this generalist approach.

This generalist approach creates a unique set of challenges: UX designers must be competent across multiple disciplines and excel at stakeholder management. They need to possess sufficient knowledge in each aspect of UX while developing enough domain expertise to make informed decisions, even without being deep experts in every area.

When you step into your first solo UX role, it’s natural to look for guidance from established UX resources. But you typically find best practices built around ideal scenarios: extensive user research, iterative prototyping, design sprints, and regular usability testing. And while these are all valuable practices, they often assume you have the time, budget, and organizational buy-in to execute them properly.

The reality is a lot messier. You’re juggling multiple projects with competing deadlines. Your “research” is whatever you can squeeze in between meetings. Developers are already coding up features before you’ve had a chance to mock up a prototype. Meanwhile, your company thinks UX is more for “making things pretty” than a strategic advantage.

Being a successful solo UX designer isn’t just about knowing best practices, although they certainly help. It’s about knowing when and how to use them to your advantage. You have to learn to make compromises while still delivering value. Sometimes, that means doing guerrilla research instead of formal studies or creating rough sketches on a whiteboard instead of high-fidelity prototypes in Figma. You have to find the sweet spot between the ideal and the impossible.

Now, there are some excellent resources out there for solo UX designers:

“The User Experience Team of One: A Research and Design Survival Guide” by Leah Buley and Joe Natoli

“Lean UX: Designing Great Products with Agile Teams” by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden

I could not recommend these books enough. They are stuffed to the brim with wisdom, strategies, processes, and frameworks — many of which I use myself. This article won’t critique these excellent resources or provide another “tools and methods” guide. I want to share the practical realities I’ve encountered during my 10+ years of experience as a solo UX designer, and I hope these insights might help others in similar situations.

A bit about me

I’m certainly not a UX influencer or a Google designer. What I hope to offer comes from over a decade in the trenches, working as the sole voice for UX across several diverse web development roles. I’ve worked in frontend development, designed interactive touch screens, managed several large university websites, and led design system initiatives at a major healthcare organization. I’ve designed component libraries, built countless web applications, and championed user experience in companies ranging from 20 to 10,000+ employees. I’m not here to introduce the next innovative design framework. Instead, I want to bring some practical insights from years of being the “UX team of one” across vastly different organizations.

Finding your place

As a solo UX designer, you could report to various leaders. I’ve answered to IT managers, software managers, marketing directors, assistant deans, enterprise directors, you name it. While most roles will have a clear reporting structure and well-defined responsibilities, you exist in a state of “structured chaos.” You are a service provider to multiple teams, a product or software development team partner, and frequently the sole advocate for human-centered design thinking.

Your first challenge is figuring out where you truly fit in the organization. While you might report to a specific product or engineering manager, your work touches multiple teams and projects. This structure creates an immediate struggle: you have a formal reporting structure, but your influence must extend far beyond it. Unlike developers who can focus on their assigned features and bugs, you’re responsible for maintaining a consistent user experience across the entire product landscape.

Being the only UX designer means that every design decision should ultimately fall to you, which is both empowering and overwhelming. You don’t have a senior designer to validate your choices, no design team to brainstorm with, and no junior designer to handle smaller tasks. When developers and product managers have conflicting opinions on design direction, you must be confident in defending your positions while remaining open to valid technical or business constraints.

Your organizational support system

Your direct manager should be your most important relationship. They’re not just your supervisor — they should be your advocate in meetings you can’t attend, your defender when allocating resources, and your translator to upper management. I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have managers willing to listen to my design expertise and help champion user experience to executive leadership and other teams in the organization. A manager who understands and values UX can help create the organizational space you need to do your best work. A good manager should:

Shield you from unnecessary meetings and interruptions

Help prioritize design requests across teams

Advocate for design resources and tools

Support your professional development needs

Back you up in challenging design discussions

I know that isn’t everyone’s experience, and in a later section, we’ll discuss what to do when others on your team resist listening to your ideas.

Managing relationships across multiple teams requires special attention. Each team has its priorities, ways of working, and levels of design maturity. Some teams may be grateful for your input early in their process, while others might see design as an obstacle to getting their product shipped quickly. Several teams I work with gladly chat back and forth with me regularly when working on designs for their requests, while others don’t respond with feedback until the final solution is out there.

Successfully fostering relationships with other teams requires you to:

Build trust through consistent, reliable delivery

Understand each team’s priorities

Establish transparent processes for design requests and feedback

Maintain communication channels even when you’re not actively working with a team

The key here is to remain flexible but establish clear boundaries. You need to be responsive to immediate needs, but continue to protect your time for strategic design work. Maybe more importantly, you need to help the rest of the organization understand that good design isn’t just about making interfaces “look better” — it’s about creating products that focus on user needs while still meeting business objectives.

Fighting for the user

As a solo UX designer, you’re typically the only person whose primary job is to advocate for users’ needs. Others might care about the user experience but have competing priorities — developers focus on technical requirements, product managers on business metrics, and stakeholders on deadlines and budgets.

One of the most powerful tools available is making user needs as straightforward as possible. It’s infinitely better to show than to tell. I often get resistance when I try to advocate for users, but I don’t have the evidence to back it up. Some potential ideas:

Share specific user stories and scenarios to illustrate pain points

Use data from support tickets, abandonment rates, and user feedback to highlight struggles

Create quick recordings of users (with their permission) struggling with existing features

Turn qualitative feedback into quantitative data when you can

When our team redesigned a primary clinical documentation tool, we needed to decide which “quick links” to display near the top of the page. Using analytics data from the existing solution, I made a valid argument for the top 6 search requests. By showing that these specific items accounted for most searches performed, the decision became less about stakeholders’ personal preferences and more about responding to clear user behavior patterns. This data-driven approach strengthened the design argument and helped streamline the approval process with stakeholders who initially had a different opinion about which links deserved the most prominence.

Building a compelling case for a solution is often more complex than identifying the problem. Your success depends on relating UX improvements to things stakeholders are concerned about — business metrics, cost savings, and reduced support burden. When you propose a solution, be transparent about trade-offs and back up your recommendations with data and user feedback. Making abstract UX concepts more tangible and meaningful to stakeholders is essential.

You’re going to face plenty of pushback along the way. Teams — sometimes your own — will tell you there’s no time for research, or they’ll claim they already know what users want. Start small — use whatever research methods you can, break down significant changes into actionable steps, and look for quick wins that bring value. Follow up on your recommendations, document successes or setbacks, and maintain positive relationships even when disagreeing. Choose your battles carefully. Your goal is to focus on the issues that genuinely impact users.

Building trust & managing resistance

Occasionally, you’ll find yourself on a team with developers who feel they don’t need to run UX decisions by you. It’s a delicate situation requiring good communication and a bit of diplomacy. Try to understand the developer’s perspective and workflow. It could be one of a list of reasons, including:

They want to move quickly and see design as a bottleneck

They might feel confident in their UX abilities based on experience

They may not fully understand the value a UX designer brings to the process

There might not be a straightforward process in place for design collaboration.

Rather than being confrontational, my advice based on experience would be one of the following:

Schedule a 1:1 meeting with the developer to better understand their process and share your perspective. Say something like, “I see you’ve been coming up with some UX solutions. I’d love to hear more about your process and see how we could collaborate to improve them.”

Acknowledge their solutions while offering improvements. Say, “I like how you approached X. Have you considered that users might struggle with Y?”

Establish a quick 15-minute design review process. I’ve found having regular “office hours” is an approachable option.

Promote yourself as a resource rather than a gatekeeper. Say something like, “I’m here to help make your implementations more user-friendly and consistent with our brand/design system.”

If none of these solutions work, you should raise the issue with your direct manager or team lead.

Building trust and credibility within an organization takes time, especially if UX isn’t a huge priority. The best place to start is to get quick wins demonstrating immediate value. Focus on obvious pain points that developers and stakeholders already recognize. Then, document and share specific metrics showing the impact (e.g., reduced support tickets and improved task completion rates). Learn and align with your developers’ workflow. You don’t need to be an expert to learn their tech stack and constraints, but it will help you present solutions in a way that considers technical implementation complexity. Consider making your process visible and collaborative. Share your thinking and findings regularly, not just in the final design, and get developers involved early in the design process to get their technical input. I share everything I work on in Figma with a core group of frontend developers who give me great feedback on the complexity of the technical implementation. Finally, take on a strategic design role. Connect the organization’s business goals to UX improvements. I always document my organization’s mission, vision, and values — if they exist — and ensure every decision I make aligns with one of those values.

Navigating the daily chaos

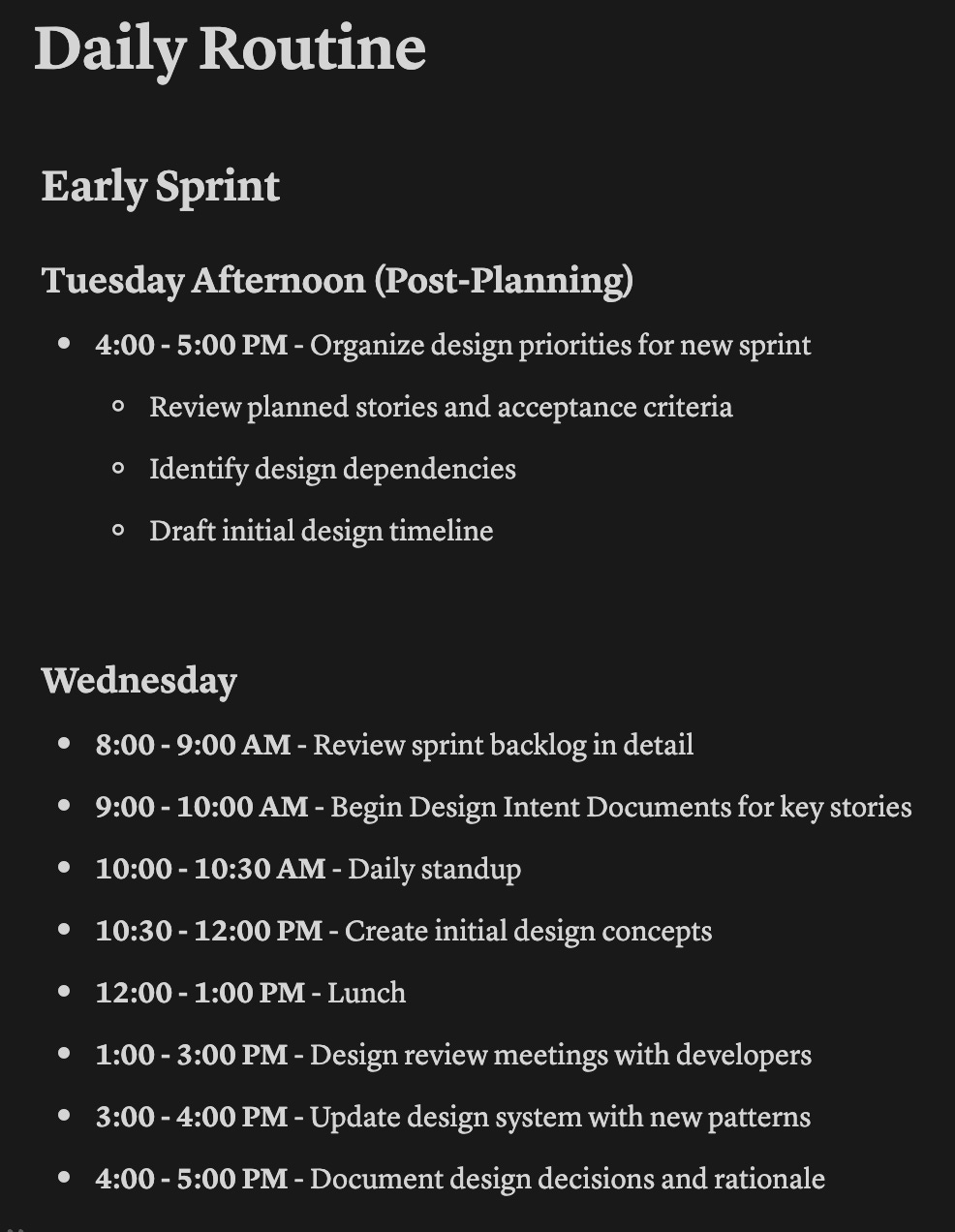

So, what does a solo UX designer’s day-to-day life look like? Each day is often different than the last, depending on how many projects you’re involved in. Some days, I can achieve a few hours of deep design work. On other days, I’m stuck in meeting after meeting, constantly pinged on Teams, and have to switch between several projects. I’m researching one minute and the next, fixing a bug in one of our UI library components. I suggest structuring as much of your day as possible. I start my day by reviewing design requests or bug reports and triaging what needs the most attention. I recommend blocking time on your calendar for focused design time and profound work. Schedule regular check-ins with developers working on implementations to help everyone stay aligned. I am working on a Scrum team, and the daily standup is a great time for this. Do your best to set aside time for user research and collecting feedback, even if it isn’t very formal.

Create a framework to evaluate incoming requests and manage the workload. Now, this might be out of your control if you’re part of a team following Scrum where you aren’t directly responsible for the work pulled into the Sprint, but this will at least help you to inform your team’s product owner of the UX value of each request. I would consider figuring out the following:

How many users are affected, and how severely?

What’s the potential ROI or strategic importance?

Are both design and development time required?

Will this create future problems we’ll need to fix?

Your time and attention are finite resources. While you’ll never be able to eliminate the chaos, having a structured approach to prioritizing work helps maintain some sanity and allows you to deliver as much value as possible. I’ve found that being transparent with your manager and/or product owner helps manage expectations while building trust — it helps them understand you’re deliberately focusing on priorities instead of arbitrarily choosing what to work on. Most importantly, saying no or pushing back on timelines is okay when appropriate. I have no problem pushing back on something I think will harm the user experience; sometimes, that involves difficult conversations about what to do while maintaining a quality product.

Flying solo

For many designers working solo, day-to-day work involves navigating a complex environment where you might be the only advocate for human-centered design. Some organizations can boast entire design teams with dedicated researchers. Still, you’re more likely to find yourself being the only one who “speaks UX” in meetings, making crucial decisions without feedback from other designers, and educating stakeholders while trying to up-skill in your spare time.

This isolation can take a toll, breeding self-doubt and even impostor syndrome, especially when there’s no senior designer to validate your work. If this sounds like you, I highly recommend trying your best to find a trusted group of peers and mentors. Whether these are coworkers with some design experience or interest, or from online communities, is up to you. I’ve been able to rely on a group of developers on my team who have experience with frontend apps and content management systems that I reach out to when I need to validate ideas. Feel free to even message me on X if you are looking for a designer peer of your own.

Confidence in decision-making is critical when you’re the only voice advocating for users. It isn’t about being right all the time — it’s about developing your decision-making framework so that you’re able to validate your solutions through user insights, business goals, and design principles. Over time, you’ll trust your experience more and be receptive to feedback.

Creating organizational impact

Your measure of success as a solo designer isn’t just in the solutions you create but in how you transform the organization’s approach to design. Building scalable systems rather than one-off solutions is critical, including making a comprehensive component library, transparent documentation practices, and developing reusable research templates. Look for opportunities to share your design knowledge across teams. Small, consistent actions will add up. Over time, these efforts can shift the organization’s mindset from seeing design as just a service to recognizing its strategic advantage. No matter the roadblocks or resistance I encounter, nothing will stop me from advocating for accessible, human-centered solutions in every aspect of the organization.

Key Takeaways

Focus on building relationships with key stakeholders, especially your direct managers, who can advocate for UX initiatives on your behalf.

Back up design decisions with data and user feedback whenever possible — showing is more effective than telling.

Develop a framework for evaluating and prioritizing incoming requests to manage workload effectively.

Build scalable systems (component libraries, documentation, templates) rather than creating one-off solutions.

Find ways to demonstrate immediate value through quick wins while working toward longer-term strategic goals.

Maintain professional development through peers and online communities.

Choose battles carefully — focus more on issues that genuinely impact users and remain flexible on less critical matters.

Make your process visible and collaborative, involving developers and stakeholders early in the design process.

Structure your time intentionally, but remain flexible to the inevitable chaos.

Focus on transforming the organization’s approach to design through minor, consistent improvements.